This is El Péndulo. I’m Julio Vaqueiro.

During this series we have taken you to North Carolina –

Pastor Daniel Sostaita: I mean, I see that we build walls and not bridges.

To Pennsylvania –

Daniel Jorge: And we believe that we are going to vote for this president because he is going to lower the price of gasoline. Is that all you are looking for in a president?

We went to Nevada…

Marta Fabiola Vazquez: People are afraid to spend now. They don’t spend like they used to, they don’t go out like they used to. Prices are very high for food, for everything.

To Arizona…

Adrian Fontes: Here in Arizona, not only in the summer – it is very hot. [laughter]

And to Florida –

Julio: And now that we are in an election year, is there anything that worries you? Anything that particularly calls your attention?

Zairenna Barbosa: That the differences have been taken as a point not to solve the problems, but to create them.

Always with the same goal, to listen to you, the Latinos from different countries, who live and work and who are part of this immense, diverse country. We wanted to understand how you planned to vote… And why. Your concerns, your complaints, your dreams.

We said it in the first episode: our idea is never to give predictions, but to report on what we found, in the streets, in the markets, in the churches, in the neighborhoods. And well, now, Wednesday afternoon while we are recording, we have something that we thought we would not have so soon… A result. A winner.

Donald Trump.

Trump: This is a magnificent victory for the American people that will allow us to Make America Great again. [applause fade out]

However you look at it, his victory is historic… The last time a president won a second non-consecutive term in the United States was more than a century ago, in 1892.

So, the man who was rejected by the American people four years ago, who was found guilty of 34 criminal charges, and responsible for sexual abuse and who continues to face other charges… today is once again at the gates of the White House.

And this time, he has a clear mandate. Unlike his victory in 2016, this time he also won the popular vote. If that were not enough, his party has also won control of the Senate. Control of the House of Representatives was still undefined at the time of closing this episode.

Let’s say that a little more than half of the country is happy with these results, and the other half, or a little less, is distressed, or even in shock.

So, to understand everything that has happened, and what it may mean for Latinos and for the country, we have two guests… Sabrina Rodriguez, national reporter for the Washington Post, and Paola Ramos, my colleague from Noticias Telemundo and author of the book “Defectors.”

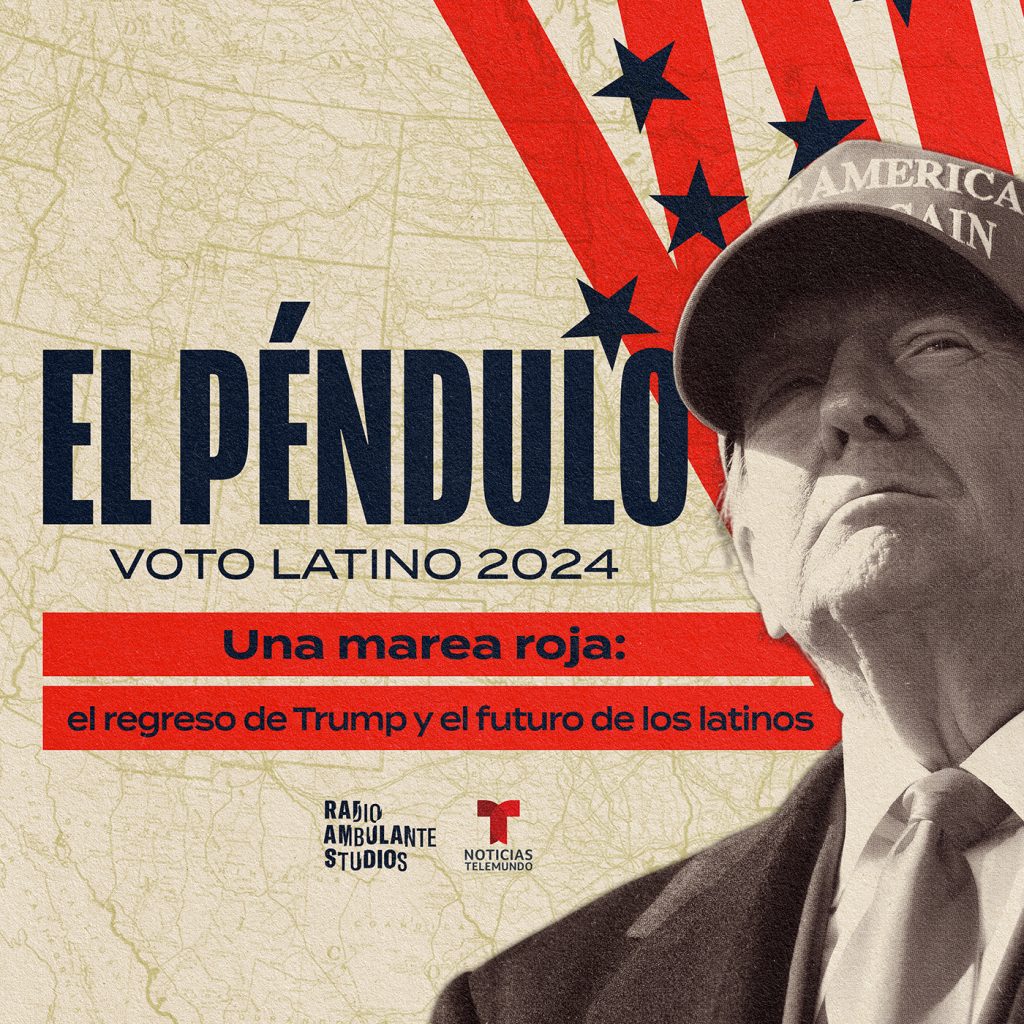

This is El Péndulo: the Latino vote from five states that will decide the presidential elections in the United States. A podcast from Noticias Telemundo and Radio Ambulante Studios.

Today… The red tide. The return of Trump and the future of Latinos.

JULIO: Hey, Sabrina and Paola. Thank you very much for being here.

PAOLA: Thank you very much.

SABRINA: Yes, thank you for the invitation.

JULIO: Well, first of all, the polls told us that this was going to be a very close presidential campaign, that the two candidates were neck and neck with a count that could last even days without us knowing who was going to be the winner. But here we are. With Trump winning the electoral vote and also for the first time, the popular vote. What do you think happened? Sabrina, we start with you.

SABRINA: I think it’s a question that we’re going to be asking ourselves for days and weeks. Honestly, I think that for example, now we’re starting to see the exit polls and seeing. Okay. What group? I mean. What are the groups that helped Trump win the presidency? So what we’re seeing now in just the hours after the election was over is that everyone —I mean, if we’re talking about various groups of Americans: I mean Latinos, African Americans, white women— helped Trump win the presidency and I think that shows us the limits of the polls really and we focus so much in the days before the election on seeing, «ah! look at 50% in this state or look at 49% in this one». But at the end of the day it all depends on who goes out to vote.

JULIO: Mhm. You, Paola. How are you explaining it?

PAOLA: Look, I think Sabrina is absolutely right. I think that now we kind of don’t know what the whole story is, what the whole picture is. But what we do know is that we underestimated the power that Donald Trump had. I think that in the last two months we thought maybe that in the face of what Donald Trump was saying, this country was a country of immigrants that in the face of these abortion bans this country was perhaps going to choose not to be pro-abortion anymore. But I think that what we are understanding right now goes far beyond Donald Trump, it goes far beyond Kamala Harris, it has everything to do with the voters, and the voters had two very clear, very different options. Two fundamentally different stories. And they clearly chose a candidate who is promising a very different vision for this country. And that’s what we have to process. What are they telling us? Maybe it’s an electorate that does care about democracy, but in a very different way than we thought.

JULIO: Mhmm. Now, the idea that we had working on this series and seeing the numbers and listening to different reports before the vote, we have the image of a country divided within different Latino communities, even where you are in Pennsylvania and Arizona. How have the Latinos you’ve spoken to reacted? What have you heard off the top of your head, Sabrina?

SABRINA: I think that. I mean, it does show how divided we remain. I mean, it’s not something that’s going to change because Trump won. I think that the divisions that exist are only going to be reinforced. And I think that coming up to the vote in Pennsylvania, I’ve been in the Philadelphia area. A lot of the focus has been on the Puerto Rican vote and for the Democrats there was a hope that they were going to win with a lot of Puerto Ricans because of the comment that was made at one of Trump’s rallies in New York, when a comedian said that Puerto Rico was an island of garbage and in the last days before the elections that was it. I mean, they used it as a moment to really mobilize voters and there was a hope among the Democrats that it was going to help them. But then, talking to voters, I met several Puerto Ricans who voted for Trump, who were saying that yes, he offended them, I mean, they were offended by what had been said, but that at the end of the day they were more concerned about the future of the country, that they were really more concerned about the economy if it offended them, that sometimes they thought that things that Trump said were ridiculous and they didn’t like them, but that they thought that the future was safer with him. And I think that we are going to have this conversation again for weeks and months: that people see a very different vision of who could help us in the future. But I think that in Philadelphia it became clear that many Puerto Ricans did go out to vote. Yes, they were interested in the election, but they had different visions of who would be the person who would help their families.

JULIO: Yeah. What have you heard in Arizona, Paola?

PAOLA: Well, something similar, right? Look, I spent the night with many families of mixed immigration status. I think that at the beginning of the night, before understanding the results, before seeing that Trump had won, I think that the hope of many of these immigrant families —the hope was that at the end of the day the Latinos would support them, right? That Latinos, faced with the comments that Donald Trump had made, faced with those comments that were heard in New York about the island of garbage and the promise of mass deportations —I think that the hope that they had was that at the end of the day what happened in 2020, in 2016 and in other previous years would happen. And that is that the Latino community would come out in very large numbers in favor of the Democrats. But I think that just like what Sabrina says, we are seeing that two stories can exist at the same time, although there are Latinos who were afraid of those threats of mass deportations and who chose Kamala Harris, but even so there were many more Latinos than expected who were not insulted by Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant comments. And that was seen here in Arizona. No, it did not affect them much, they did not feel included in those insults. I think the interesting thing that’s happening here in Arizona is that even an immigration proposal that was on the ballot, which is Proposition 1314, which is a proposition that gives, that will give more power to local police here so that they begin to act as immigration agents. That proposal here in Arizona, in a state where there are many Latinos, won. So we’re back to the same thing. We’re facing an election where many stories can exist at once.

We’ll be back.

[MIDROLL]

We’re back at El péndulo. I’m Julio Vaqueiro.

Today we spoke with my colleague Paola Ramos, from Noticias Telemundo, and Sabrina Rodríguez, national reporter for the Washington Post.

JULIO: Well, one of the big stories is the margin between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump. Right? Latino voters supported Trump much more in this election, 25 percentage points more than four years ago. It’s a historic change. No other Republican had reached this percentage and you have reported a lot about these communities. How do you explain it? Paola, for example, you wrote the book Defectors —just about how Latinos have turned to the right. Did you expect this figure? 45% of Latinos voting for Trump?

PAOLA: Yes, I expected it because I think we’ve been seeing some of these signs for four years. Back in 2020 we started to see that Donald Trump, after four years in the White House, already began to increase those margins with the Latino community, increasing between eight and ten points in 2020 compared to 2016. I think that in the last four years we have begun to see signs, signs of a Latino community that did not care so much about those threats of mass deportation, signs of a Latino community that felt comfortable with some of the anti-trans comments that Donald Trump’s campaign was making. We have seen a Latino community that little by little also feels much more comfortable with the evangelical movement. We have seen a Latino community, even Afro-Latino, for example, in a state like New York, that also feels more and more comfortable with some of the anti-African American comments. I think that’s what it tells us, that there are many more divisions between us than we want to see, than we want to acknowledge. So I’ve been seeing these signs for a long time.

JULIO: And Sabrina, we saw something that you posted on social network X on Tuesday, on election day, you wrote. And I’m going to translate it here. Let’s not start with that of blaming Latino voters again. Let’s see, explain to us. What do you mean?

SABRINA: Ah, Julio [laughter] The interesting thing has been the response to that post, really.

Julio: Let’s see?

SABRINA: But I think that for me. I mean, looking at the exit polls, looking at the states that Trump has won, this goes beyond Latino voters and that’s the part that frustrates me already and is going to frustrate me with the narrative. It’s that in the next few weeks it’s going to focus a lot on the US. Why is it that Latino voters gave the presidency to Trump and it’s going to be as if Latinos were the only ones who went to vote for Trump. Or it’s going to be a focus on, that is, the 45% who voted for Donald Trump instead of the 55% who voted for Kamala Harris. And I think that’s the part that many times the debate and the conversation around voters and Latino voters in particular, lacks that level of complication of talking about the differences, the divisions, that in one area it can be different than in another. I mean, we talk and we’re probably going to talk more, but about the division between women and men. I mean, there are so many, there are so many pieces of this conversation and I think it’s irresponsible, I mean, to put all the blame on one group for what happened in this election because Trump won.

JULIO: Also, it’s interesting the approach of blaming someone for voting, no, for what they wanted.

SABRINA: Absolutely. And I think that —and look, I think that seeing what I’m seeing in X, there are many people. I mean, they voted for Kamala Harris, who are blaming Latinos. I see it in the comments on that particular post. People saying, “Well, Latinos deserve to be deported. Oh, look, they deserve what’s going to happen now, because look how they went out to vote for Trump.” And I think that because of comments like that, because of responses like that, we are in this moment of so much division. I think that also, I mean, Democrats have to take a moment now after this and well, more than a moment to really process why this has happened and what they have to do differently. Because Pablo and I have talked about it many times, but after 2020 there are many Democrats who came out saying that the exit polls were wrong, that there weren’t that many, many Latinos who went to vote Republican or they blamed themselves, I mean, the Mexicans in South Texas, in the Grand Valley River or the Cubans in Miami. But always. But it was not possible that Trump was doing better with Latinos around the country. It had to be a group here, a group there. But it is not. I mean, it is not something that is happening in the rest of the country and I think that in having that reaction. They have been very late in responding to this problem that they clearly have when we are talking about a group of people that for decades were expected to be voters, that the Democrats could depend on.

JULIO: Do you agree with this vision, Paola?

PAOLA: Totally. And look, there is also something very interesting. I mean, all the comments right now are going to be focused on the Latino community. What happened? But that is the reality. The reality remains that regardless of the fact that Kamala Harris won the Latino vote, she also won the African-American vote. And the reality also remains that white women who were supposedly going to be the Democrats’ salvation at this moment, white women continued to vote for Donald Trump. So this idea of blaming groups really starts with that reality that white women continued to support Donald Trump. Despite all this narrative and despite the threat of abortion bans, I also think that what Sabrina says is very important. One of the things that is very clear here in a state like Arizona and it is what activists would tell you, what many Latinos would tell you is that here the Democratic Party failed them. They did not give them the resources they needed, they did not give them the infrastructure they needed. And I think that more than anything many Latinos on the left would tell you that they did not give them the message they needed to mobilize, to inspire a coalition that right now needed to be inspired, they did not need to have a message that would lead them to that final goal.

And what do I mean? I mean this idea that if we think about 2020, one of the reasons why Joe Biden wins in a state like Arizona is because he distanced himself in a very, very clear way from Donald Trump’s cruelty at the border. If we remember the last two weeks of that campaign, in 2020 we saw a Joe Biden who promised immigration reform, who was not afraid to insult Donald Trump very clearly and very aggressively against his immigration plans. I think that in the last two months we have seen a candidate, Kamala Harris, who is much more moderate, much more conservative with his immigration plan. And perhaps we have to ask ourselves what would have happened if the vice president had put forward a message, perhaps a little more progressive and perhaps a little more inspiring and perhaps a little braver in terms of that immigration message. I think that is something that many Latinos here are thinking about.

JULIO: It is an interesting question. What other questions are there that you think can help us understand this Trump victory? Sabrina, what other questions do you think are worth asking ourselves? Or the Democrats, specifically, asking themselves?

SABRINA: Yes, well. I think that there are several questions that we can ask ourselves about immigration, and I think that Julio, I mean, you yourself asked the vice president the question that stayed with me when you said to her: “So, has Trump won the immigration debate?” And she said absolutely not, but the reality is that in her campaign she hardly talked about immigration. It’s not just that she took a more moderate position, she didn’t talk about it much. So I wrote an article recently that I was looking for data and the Republicans spent 243 million dollars on ads about immigration, while the Democrats only spent 15 million dollars. I mean, it’s a big difference. So, if we talk about four years of, I mean, people listening, of being afraid of immigrants, of the situation at the border, I mean the image that was painted of a border in chaos, of people entering an open border, and then there is no message on the other side because it’s nothing more. I mean, again, it’s nothing more than… Ah, yes, the message was moderate. If she was talking about things like the Republicans. I mean, it was almost not being talked about. I think it’s something that, again, the Democrats have to really analyze how they are going to be. I mean, what is the message on immigration in the future? And beyond that, I think it’s also going to be how we talk, how we go, how the Democrats are going to talk about the economy, how they are going to talk to the working class? I mean, it has been seen, we see, that there are people who did not graduate from college or who are working class have moved more towards Donald Trump than the Republican Party. It is being seen more as a party that represents those people. Historically it was not like that. So there are many questions to ask about how we got to this point and how that can be changed for the Democrats in the future if it is going to stay that way.

JULIO: Well, because we already saw that Trump’s victory is based on winning the largest percentage of the Latino vote, but also a larger percentage of white women. Also more men, more whites, more young people, more African Americans. And what does this say about your campaign, Paola, about Trump’s vision of the country?

PAOLA: Well, that’s the million-dollar question, huh? I don’t know. I mean, I think it simply indicates that this is a country in which these figures who perhaps present themselves as more authoritarian are not bothered by that image. I think that what people are also telling us is that this message that Trump had, not of them against us, the others, being the immigrants. That message resonated a lot, right? So I think we have to start there. And I also think that perhaps we have to present ourselves. We have to present ourselves with a question that may make us uncomfortable. And that is this idea of whether perhaps this Latino community that we thought was a united community. A community that had a lot of solidarity. Yes, perhaps we are already seeing a community that is much more fractured than we want to accept. And if perhaps we are already seeing two Latino communities, right? And we also have to ask ourselves if we are at a moment where we can unite a country that is very divided, and I have many questions because Julio, I really don’t know what the answers are less than 24 hours before these elections, I don’t really know what the country is telling us. I think we will know a lot more on January 20, when Donald Trump is in the White House, when we begin to see these massive deportations, when people begin to understand well what these deportations mean. What it means for someone in a Donald Trump administration to look at us Latinos and decide, «Ok, you look like you are an immigrant. You look like you are undocumented». Once people understand that, that is where I really want to see. If those Americans who voted for Donald Trump are going to feel comfortable in that type of United States.

JULIO: Yeah. Yes, it is still early. You’re right, it’s only been, well, not even 24 hours —I don’t know— and we’re recording this podcast.

PAOLA: Like Sabrina said before, this is like therapy for us, to understand well, to understand well and process. Of course.

JULIO: If there’s something that also needs to be explained —the Democrats, the campaign of Vice President Kamala Harris bet a lot on the issue of reproductive rights, which would be key to mobilizing the female vote and in states like Montana, Nevada, Missouri, amendments to protect the right to abortion passed. But at the same time, voters in each of those states elected Donald Trump. How do you explain that, Sabrina?

SABRINA: These are all difficult questions today, really. Look, I’ve spoken to many voters who don’t blame Donald Trump for what happened with Roe versus Wade. I mean, it’s the message he’s given on the issue of abortion, on the issue of reproductive rights. The first one for many months. This year it wasn’t clear what his position was. I mean, he did like sometimes he would come out and talk about how he was glad that he took, you know, the responsibility for the overturning of Roe versus Wade. And then on the other side, then he would come out and say that some of the places, you know, the bans that had been put in place, that he didn’t agree with, that it was too much. So, he kind of navigated it so that it wasn’t very clear what his position was. And then at the end, he would talk about how he promised that he was not going to pass a national ban on abortion. So I think for some voters it was like, oh, well, I can vote in my state for, you know, to protect this right or to give this right back and I vote for him, because he’s not going to do anything at the national level. And I think that there is, at the level of confusion, that is, the lack of clarity about why we got to this point on this issue of reproductive rights, why it is that in 2024 we are talking about it, we are talking about it because Donald Trump put people in the Supreme Court, judges who took away that right. But I think that many people do not, they do not understand that, they do not know that. And so it has been focused – Okay, well, if I have, that is, if I can vote this time to protect it, I will protect it. And why not?

JULIO: Yeah. Now we were listening to Paola talk a little about this, about the mass deportations that are the flagship proposal of this Trump campaign, eh? But it also requires an explanation, right? How, despite this promise starting on the first day of his administration, Trump had historic support among Latinos. How do you explain that, Sabrina?

SABRINA: I think that again, a lot of what I say is based on months of talking to Latino voters in different key states. And one of the things that I have seen is that many people, I mean, they don’t take what he has said to his face. Many people think that, well, no, he is not necessarily going to do that. And I am talking about people who were going to vote for him. Clearly there are many Latinos who voted for Kamala Harris who are truly afraid and truly believe that he is going to do what he has promised. But I say, for those Latinos who were considering voting for Trump because they already expressed that they were going to support him – talking about this issue with them, when you talked about mass deportations it was, “Well, I agree that the people who are working should stay or I agree with the people who are not taking resources from the government. What I say is that we have to send the criminals away.” So it is like, well, that is not mass deportations, those are, it is not the same thing. So I think there is also a bit of a lack of education, of understanding what exactly Trump’s proposal was, because he is already talking to voters who were going to Trump’s meetings. There are many who say that he spoke about it, that is, he spoke in very clear terms about how he feels, about undocumented immigrants and their deportation plans and the same people that I met in those meetings said what I am telling you that, “Oh, no, but not everyone. Some people do or some don’t, and they weren’t very clear about how that would work, but they wanted to see him try.” And as Paola said before, I think that the part after this is going to be what the reactions are when this becomes a reality? These are plans that have been made for years, that is, they are planned so that they can do it the moment he enters the White House.

JULIO: Paola, is it really possible to carry out mass deportations like those described by Trump?

PAOLA: We don’t know, but what we do know is that they are going to try, they are going to try and as Sabrina says, they have been planning it for years. I think one of the big things that Donald Trump regrets or one of the things that he hates is knowing that Barack Obama deported more people than he did. So I think that they have been planning for years and years what these mass deportations mean. And I think that something very interesting is that obviously these mass deportations by Donald Trump are based on the plan called Operation Wetback under the presidency of Eisenhower. What happened under Eisenhower is that they did deport a little more than 1 million, mostly Mexicans, but what was seen during those years, Julio, which is interesting, is that they also ended up deporting Mexican American citizens who ended up being deported because of the way in which they were racially discriminated. That is to say, it was an administration that looked at the public and ended up saying, well, you look like you are Mexican, so you are going to be deported too. That is history. These are statistics that are real. And what was also seen in those years was that at first the American and Mexican community was in favor of these mass deportations and what happened after three or four years is that the Mexican American community ended up being against these deportations, when they realized that it was affecting them. And now we are living in a United States in which immigrants are already Americans. That is, we live in a country where there are more than 22 million people who live in mixed-status families, more than 10 million American citizens. That is, now we are talking about mass deportations that are not only going to affect immigrants, but American families. So is it going to happen? We don’t know. Are they going to try? Absolutely.

After the break, how much did the Latino identity matter when it came to voting in these elections? We’ll be back.

[MIDROLL]

This is El Péndulo, I’m Julio Vaqueiro. We’re talking with my colleague Paola Ramos, from Noticias Telemundo, and Sabrina Rodriguez, national reporter for the Washington Post.

JULIO: Let me change the angle a little bit. Because we were talking about this gender gap. Right? The difference between men and women in this election. Clearly, men, Latinos, did vote for Trump by a majority. According to NBC News exit polls, 54%. How do you understand the difference in the term gender and the role of masculinity for Latinos, Sabrina?

SABRINA: That was a big focus of Trump’s campaign. He has focused on this idea of, I mean, the gender stereotypes. He has spoken very clearly in his speeches about how he is going to be the one to protect this country, that he is going to protect women. He has spoken. I mean, he has criticized women very directly. I mean, in ways that I don’t repeat about women or Kamala Harris, specifically Nancy Pelosi, has been talked about. I mean, she has a history of talking about women in some way and… And I think that in the strategy of this campaign we have seen that focus on men. I mean, going in those that are focused on men. I mean, we saw him in the last few weeks going on Joe Rogan’s podcast, which is very well known for being popular with American men. And I think that in the Latino community in particular, he has focused on a message of… Again, protecting women that the man is who he is, that is, the leader of the family of the house. And this idea that he was a great businessman who ran his company and look how he got rich and… And he has wanted to project that image towards Latino men to show that… Look, I am a person – I mean, you can idolize me. Me? I mean, if you look at me. Look, you also want to bring your family forward. You want to be a hard worker. I was a hard worker and look where I got to. And oh, dear, with that image you attract more Latino men and it clearly worked.

JULIO: Yes. He talked about that and he talked about Trump’s campaign on two main issues, not immigration and the economy, and he based it on the premise that Latino voters and their concerns are the same as the rest of the Americans used the phrase Latino Americans. Was Paola right and in that sense did Kamala Harris’ campaign fail in something?

PAOLA: Well, let’s see, I think that economic anxiety is a real anxiety. I mean, the majority of Latino voters obviously worry most about the economy, what they worry most about is feeding their children. What they worry most about is having a roof over their houses. And I think that economic anxiety that Trump was able to talk about is… I think that worked a lot for them, but I do think that they got that key message right there, right? And that is introducing the word, as you said Julio, «Latino American.» Why? Because their campaign was based on this idea and that is an idea in which Latinos have already assimilated to such an extent in this country, that perhaps if you call them Americans, perhaps in that way you can begin to attract them more to Donald Trump’s campaign. They did not accept an idea that is very simple, and that is that now we are talking about a Latino community that has mostly changed. We were born in the United States, most of us are under 50 years old. The group that is growing the most within our community are third-generation Latinos and that word “American Latinos” – perhaps it was a very powerful word. Now, I think that Harris’ campaign also tried to do the same in some way, perhaps in a slightly more subtle way. I think so. It was a campaign that understood from the beginning that being Latino in the end does not mean that we are different from any other people, we care about the same things, we care about the economy, we care about our health, we care about our security. But I think that Trump’s game of us against them, them being the immigrants, is a strategy that is based on creating fear, creating terror, creating resentment. That strategy is based on emotions and I think that worked very, very well for them.

JULIO: But I also think that the big question is, do we now have to stop thinking about identity as a fundamental point for Latinos when it comes to voting? And if so, what does it mean for the future of the Democrats? No, Sabrina?

SABRINA: That’s the question. That’s the most key question. It’s that. I mean, I have to laugh a little because we’ve talked about it in recent years about what the Latino voter means? What is the Latino vote to me? I think that today more than ever I don’t have the answer. Today more than ever I don’t know. I don’t know what to say. I mean. What? What is the answer? What unites us? What unites us as Latinos today? I really don’t have that answer, because based on what we’ve seen in the difference between Latino men and Latina women, that is, the percentages are so close. I mean, it’s historic that Trump, yes, yes, the exit polls remain at these levels of 45%. It’s historic that Trump wins with the Latino voter. So, I think there are a lot of questions about what the message to Latinos is going to be in the future. But I think one of the most important things here is, I mean, what I don’t want to see is that Democrats and Republicans now do nothing or that Democrats say, oh, well, now the Latinos have gone to the Republicans. We’re not going to try, we’re so close. I mean, almost. They’re going to win. Most of us don’t do anything. I think what it reinforces is that they have to really try with the Latino voter, that they really have to try to understand the same way they tried to get white women to vote. It didn’t work for them for one reason or another, but I guarantee you that in the next election they will still try to get the white women out. And what I don’t want to see is that there won’t be this investment, this attention, this concern about Latino voters going forward.

JULIO: Yes, in any case what it shows is that you have to work for the Latino vote and it’s not guaranteed for anyone, right? Well, the campaign is over now. The election. The two of you covered it very closely for months. What would you say you have learned about the country in this process, Paola?

PAOLA: Well, well, first I don’t know if anything is over. I think at this moment. Maybe. Maybe everything is just starting. Sabrina, I think, hasn’t been home for how long?

SABRINA: Months.

JULIO: Yes, she posts Instagram photos.

PAOLA: Yeah. Well, look, I’ve already learned that maybe my work should be much more focused on listening. I mean, I think we are journalists who are used to asking questions, maybe to having very clear stories, but I think we are at a time where we have to listen to the country. We have to understand what the voters are telling us and I think that is a very difficult job because we have to leave all these stereotypes aside. We have to leave politics behind.

One way, we have to put these countries aside and listen and do and just listen so that people are not afraid to tell us exactly what happened. So I’m not answering your question, Julio, because, like many of the questions you ask me, I don’t have a very clear answer right now, but what I do know is that to understand what I’ve learned I have to keep listening more.

JULIO: No, I love it. Sabrina, you?

SABRINA: I think that what this election has shown me is how complicated each person is. I mean, my grandmother always has an expression that each person is a world. And I think that this lesson shows us that, because I have spoken with so many people who, I mean, their opinions on how they see the country, how they see the different issues that have been or have been focused on in this lesson, the candidates see things. I mean, they see things differently. I have spoken with the person who, I mean, supports reproductive rights and who is so, so frustrated with what has happened on that issue in this country in recent years. But at the same time, they were going to vote for Donald Trump because of the immigration issue or because of the economy. And I think where we can fail here in the conversation in the months after this is to think that ah, so all Latinos are conservative and I think there may be Latinos who feel anxiety about the economy, who are also worried about climate change, who also want to see the rights of transgender people who are also supporting, that is, reproductive rights. I think that each person can see the world in so many different ways and I think that is what I have learned, is that you can never. I mean, you have the idea of ah, this voter thinks like this, this one like that, but no, no, and I think that in the conversation I want us to continue talking about not just the polls. But what is behind those polls? What are the conversations that Latino families are having today and in the coming months?

JULIO: Sabrina and Paola, thank you both very much.

SABRINA: Thank you.

PAOLA: Thank you.

Sabrina Rodriguez is a national reporter for the Washington Post.

And Paola Ramos of Noticias Telemundo and author of the book “Defectors.”

[MUSIC]

El Péndulo has been a co-production of Radio Ambulante Studios and Noticias Telemundo.

I am the host, Julio Vaqueiro of Noticias Telemundo. This episode was produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess [bir-jess] and Jess Alvarenga. Editing is by Daniel Alarcón, with Eliezer Budasoff and Silvia Viñas.

Desirée Yépez is the digital producer. Geraldo Cadava is an editorial consultant. Ronny Rojas did the fact checking. Music, mixing and sound design are by Andrés Azpiri. Graphic design and art direction are by Diego Corzo.

At Noticias Telemundo, Gemma García is the executive vice president, and Marta Planells is the senior digital director. Adriana Rodriguez is a senior producer, and José Luis Osuna is in charge of the video journalism for the series.

At Radio Ambulante Studios, Natalia Ramírez is the product director, with support from Paola Aleán. Community management is by Juan David Naranjo Navarro. Camilo Jiménez Santofimio is the director of alliances and financing. Carolina Guerrero is executive producer of Central and the CEO of Radio Ambulante Studios.

El Péndulo is made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, an organization that supports initiatives that transform the world.

You can follow us on social media as @ [at] central series RA and subscribe to our newsletter at centralpodcast dot audio.

I’m Julio Vaqueiro, and thank you for listening.